Does Suffering-Focused Ethics Valorize the Void?

Richard Y. Chappell urges us not to “valorize” the void. According to Chappell, any adequate moral framework must recognize the existence of positive intrinsic goods and not focus solely on bads. Utopia, he contends, is clearly better than an empty void, and it should be table stakes for moral theories to acknowledge this.

Suffering-focused ethics (SFE) holds that reducing suffering is a foremost priority. It is primarily concerned with reducing bads rather than promoting goods. Given its focus on bads, one might wonder what suffering-focused ethicists think about empty voids. Might they “valorize” them?

The empty sky

A Family of Views

It is crucial to remember that SFE is not a single theory but a family of views united by the strong priority they assign to reducing suffering. Many positions under the SFE umbrella do not in any sense valorize the void. Many suffering-focused ethicists, for instance, hold that positive value exists and should be promoted. They are skeptical, however, that such value can compensate for or outweigh the negative value of suffering. They may think that (extreme) suffering matters significantly, or even lexically, more than happiness, pleasure, or other positive goods—though the latter still matter.

Suffering-focused ethicists with this view would prefer a utopia of happiness to an empty void. The only requirement is that the utopia be a genuine one. If it contained (extreme) suffering, the suffering-focused ethicist may no longer regard it as utopic. And she may well prefer a void to that.

Other views in SFE are grounded not in an asymmetry about value between suffering and positive goods like happiness but in an asymmetry about duties or moral reasons. Even if happiness and suffering were mirror images of each other in terms of their intrinsic value, our duties and reasons for action concerning each may not be.

Suffering, many hold, makes demands on us that happiness does not. We may have a duty to relieve others’ suffering. Yet one who is already happy may have no claim, or a far weaker claim, to be made even happier. This view is compatible with the claim that happiness and other positive goods matter intrinsically, and that a utopia would be better than a void.

Minimalist Views

The precise targets of Chappell’s objection are views that deny the existence of intrinsically positive value. Minimalist theories—such as those developed by Teo Ajantaival and Lukas Gloor and which draw on Buddhist and Epicurean traditions—understand well-being not as the surplus of goods over bads but simply as the absence of bads. These bads may include suffering, preference frustrations, and harms such as restricted autonomy, violence, and other violations.

These views may sound deeply counterintuitive to some, but they may become more intelligible when we look closely at the phenomenology of pleasure. Much of what we call positive experience may be a relief of negative experience rather than an independent good. If pleasure is mostly about the quenching of cravings and disturbances, perhaps the highest form of well-being is tranquility, the kind of serene fullness in what the Greeks called ataraxia or the Buddhists nirvana.

Regardless of whether we find minimalist views plausible, we may ask whether they really “valorize the void.” The truth is that they do not, at least not intrinsically. The phrase gives the impression of valuing it for its own sake. But what suffering-focused ethicists value about the void is simply its absence of suffering—and that does not require a void at all.

A utopia overflowing with joyful life could just as well lack suffering, and if it did, the minimalist would regard it as among the best worlds. The crucial point is that what she values is not the void itself, but what the void contains—or rather, what it does not.

Other Views Are More Counterintuitive

Chappell may still find it counterintuitive to be indifferent between the void and utopia, even if the void itself is not valorized. Perhaps you agree with him, even after reflecting more deeply on minimalist views. But it should also be noted that competing views have very counterintuitive implications in this area. Take total utilitarianism, which Chappell is sympathetic to. It would recommend turning empty voids into torture chambers, so long as there were many beings with lives barely worth living to supposedly compensate.

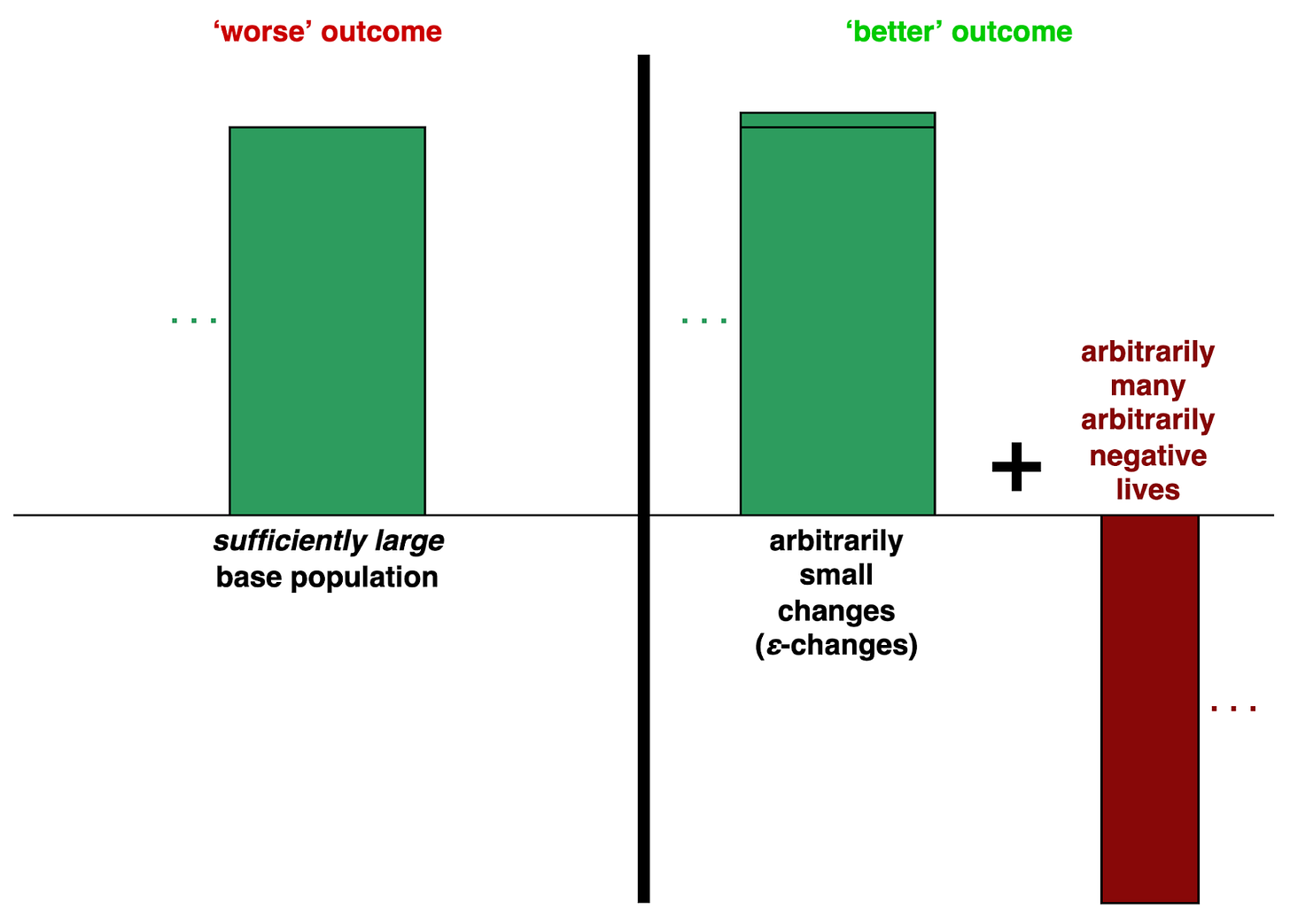

This is the so-called “very repugnant conclusion.” There is also the related implication of “creating hell to please the blissful”: according to total utilitarianism, it would be an improvement to add a population of maximally hellish lives in order to bring a sufficiently large population of almost maximally blissful lives to maximal bliss.

The above image, from Teo Ajantaival’s post, depicts “Creating hell to please the blissful,” which suggests that the outcome on the right is better than the outcome on the left.

Compared to consistently preferring worlds with less suffering, it is arguably less plausible to endorse such torment-for-pleasure tradeoffs.

Conclusion

The charge of “valorizing the void” addresses only minimalist views rather than suffering-focused views in general. As we have seen, one can be a suffering-focused ethicist while preferring a populated utopia over an empty world. Yet even regarding minimalist views, the charge misframes what those views actually value. Suffering-focused ethicists do not valorize the void. What they valorize is a world—large or small, empty or full—with less suffering.

Hmm, how about this thought experiment, related to valorising the void:

Imagine we were in 4 billion BC. Right before the dawn of life. Suppose that by pouring bleach into this lake over here (let's pretend no aliens exist, and pretend all life originates from micro organisms in this lake, etc.), it would result no life ever existing (this great epic, this 4 billion year unfolding (full of immense suffering—and let's suppose it's net-negative, with suffering exceeding flourishing and joys), would not happen. And no life would exist forever.) You are a disembodied soul/ghost with a bottle of bleach. Would/should you pour bleach into that lake?

On the one hand, it seems like the right answer is that one should not pour bleach into that lake: one should allow evolution and life to happen, warts and all. It makes for a much more interesting and varied and fantastic Universe, full of Flourishing creatures (even if the only really fully flourishing creatures would only come to exist billions of years later), full of joys and pleasures and desire satisfactions and objective values (and yes, full of suffering and pains and tortures and heartaches).

On the other hand, it seems like commitment to *any* suffering-focused ethic would logically commit you to pouring bleach into that lake and preventing evolution/life from happening (since evolution is stock full of suffering).

Your thoughts? 🤔