The Compensation Question

Can anything morally outweigh or compensate for extreme suffering?

Can anything morally outweigh or compensate for extreme suffering? This simple question strikes at the heart of ethics. Yet too often, it is neglected. It may be hard to think about this question in the abstract. To bring it into focus, let us consider a few concrete cases.

The Drowning Child

Perhaps you have encountered Peter Singer’s drowning child thought experiment. You see a child struggling in a pond; you can save them easily, though it means you will ruin your expensive shoes. Plausibly, you ought to save the child.

Singer takes this case to have far-reaching implications for our obligations toward the global poor. Failing to donate effectively to famine relief, Singer suggests, is akin to walking past the drowning child. But let us press the issue further, and broaden the case. Imagine not just a drowning child, but a child experiencing the most extreme suffering, enduring something far worse and longer lasting than drowning.

Is there anything that could be more important than helping this child? You might think that the chance to save even more children from enduring similar suffering would be more important. But is there anything other than preventing more suffering that could qualify? What pursuit, what beauty, what pleasure or progress could be more important than pulling someone out of torment, if we had the chance?

In her article “Moral Saints,” often read as a foil to Singer’s essay, Susan Wolf argues that there is more to life than morality. This view may seem appealing. It is good to be moral, but there is also art, beauty, achievement, personal projects, and relationships. Surely a well-rounded person with a rich life has many facets; they are not a moral saint, exclusively occupied with acting morally.

But instead of thinking about morality in the abstract, we should test this claim in the crucible of the case of the suffering child. That is, we should ask ourselves if we can justify pursuing the goods Wolf mentions at the expense of letting a child suffer in extreme pain. We should ask ourselves whether, for instance, we can walk past a suffering child so that we may pursue art, knowledge, or personal projects. In the end, you may conclude that you would be justified in walking past the suffering child for some such good. But perhaps, when framed this way, the question at least gives you pause.

Limited Resources

The philosopher Jamie Mayerfeld reminds us that we administer anesthesia to surgery patients so they feel no pain while being cut apart. He asks us to imagine an alternative: using our resources to instead develop a drug that heightens the pleasure of people who are already happy. If this drug could produce pleasure as intense as the suffering anesthesia prevented, would you be indifferent between these options?

If you would favor administering anesthesia to prevent the suffering, would your answer change depending on how many people were involved? Suppose, for instance, you could enhance the pleasure of one thousand Buddhist monks sitting in perfect serenity. Would you consider doing this over administering anesthesia to a smaller group of surgery patients, leaving them to suffer?

Omelas

Ursula Le Guin’s Omelas is a radiant city—prosperous, joyful, full of music and peace. Yet its happiness depends on the suffering of a single child, locked in filth and darkness. The people know this; they are told that freeing the child would destroy the city’s happiness. Many learn to accept the arrangement. Others cannot. In their moral horror, they quietly abandon the city.

This case echoes one in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. There, Ivan asks whether a good God could permit the torture of even one child as the price of eternal harmony for humankind. He steadfastly refuses to accept such a world, declaring that he will “return his ticket” rather than be complicit in its terms.

What do you make of these cases? At what price of suffering, if any, can happiness and utopia be purchased?

Utility Hogs

Next take Alistair Norcross’s case of Fred’s Basement. Fred tortures and kills puppies in his basement to extract a hormone, cocoamone, that allows him to enjoy the pleasure of eating chocolate. This seems wrong; surely, Fred’s gustatory pleasure can’t outweigh the suffering of the puppies he tortures. But suppose that Fred were a “superenjoyer” of chocolate, deriving enormous amounts of pleasure from eating it. Could his enjoyment ever morally outweigh the suffering he inflicts? Might he be justified in torturing the puppies?

Robert Nozick’s “utility monster” poses a similar challenge. Nozick’s hypothetical being derives vastly more pleasure from resources than anyone else. Could we all be obligated to endure extreme suffering if we could thereby bring such a monster immense joy?

The Gladiatorial Games

Superenjoyers and utility monsters aside: consider a more realistic case. The gladiatorial games of ancient Rome, where thousands cheered as others were torn apart for spectacle. You likely regard this practice as deeply wrong—rightly cast into the dustbin of history alongside witch trials and slavery. But would your judgment waver if you discovered that the Coliseum had been a thousand times larger than you imagined, allowing far more people to be entertained?

Scanlon’s Transmitter Room

In a similar vein, consider T. M. Scanlon’s case of the technician trapped in a transmitter room during the broadcast of the World Cup. The technician is in agony, and his torment will continue if the broadcast goes on, but stopping it would spoil the excitement of millions of viewers. Suppose the viewers would not suffer any pain or distress whatsoever if we stop the broadcast; they will only have less excitement in their lives. Should we stop it? Does it matter how many are watching?

The Procreation Asymmetry

Many believe it is wrong to bring a child into the world if we know their life will be filled with misery. Yet it seems that fewer believe it is wrong to refrain from creating a happy child. The idea that we have a duty to not bring miserable beings into existence but no duty (or a weaker one) to bring happy beings into existence is known as the procreation asymmetry. If we endorse this view, are we making a mistake? Could it really be obligatory to create happy lives? And could this be so important as to take precedence over alleviating extreme suffering?

Empty Mars

Many are horrified by the suffering on Earth and regard it as a tragedy. Yet few seem horrified by the lack of positive goods, such as happiness, on Mars. Few seem to regard this absence as a tragedy. Are we radically mistaken about this? Are we blind to a moral catastrophe occurring across our solar system and beyond, much like our ancestors were blind to the catastrophe of mass suffering? If not, does this suggest that reducing suffering is more important than bringing about positive goods, such as happiness?

The Very Repugnant Conclusion

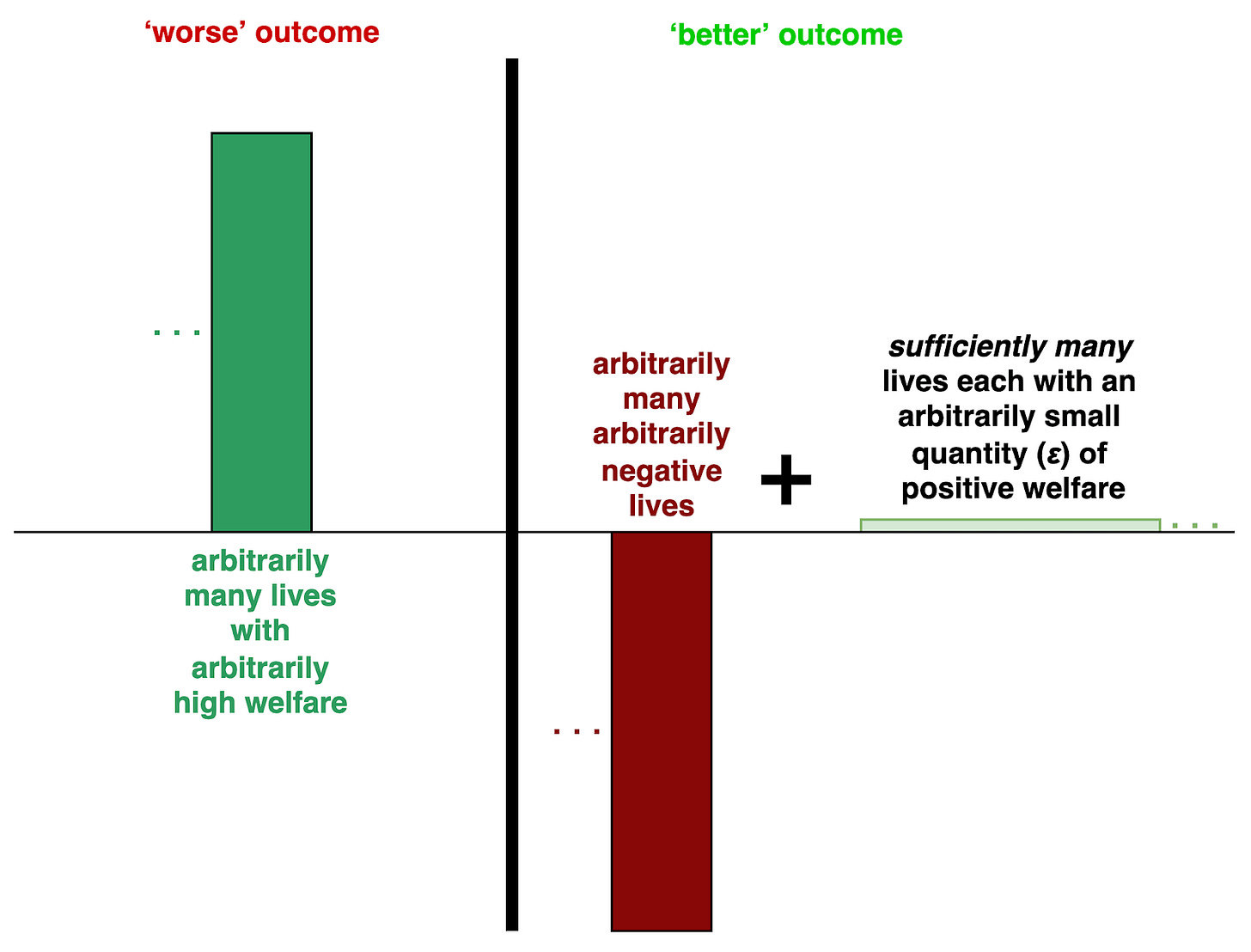

Finally there is the Very Repugnant Conclusion in population ethics. A world with billions of beings undergoing extreme suffering would be extremely bad. But could it be made good—and worth bringing about—if it also contained very many mildly happy beings?

The above image, from Teo Ajantaival’s post, depicts the Very Repugnant Conclusion, which suggests that the outcome on the right is better than the outcome on the left.

Could the outcome on the right really be better than the one on the left? If you don’t think so, perhaps this is because you suspect that happiness or positive welfare, even in large amounts, cannot outweigh severe suffering.

Conclusion

Perhaps you think that suffering cannot be outweighed by positive goods in some or all of these cases. If only in some, it is worth pressing further: why those and not others? Under what conditions, if any, can suffering be outweighed by positive goods?

Because the stakes are so high, it is vital to reflect deeply on the importance of reducing suffering relative to other goals. Too often, though, this question is passed over. This makes us liable to act in ways that, on reflection, we would not endorse. Whether we ultimately think that anything could outweigh or compensate for suffering, our first task is to bring this question into sharp relief and give it the attention it deserves.

Find your favourite thought;experiment here.